|

CHICAGO - Epidemic strains of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) have emerged as community pathogens among patients without established MRSA risk factors and are now also affecting patients in health care settings. This has implications for clinical and public health management of staph infections, and indicates a need for enhanced surveillance and strategies focusing on increased awareness, early detection and appropriate management. “It certainly is important that we continue to emphasize infection control strategies for MRSA in health care settings. Increased prevalence of MRSA in the community may impact the choice of infection control strategies in health care settings. This is an area we need to learn more about, but we feel very strongly that increased MRSA in the community is not a reason to give up on control of MRSA in health care settings,” said Rachel J. Gorwitz, MD, MPH, at the 16th Annual Meeting of the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, held here.

S. aureus resistant to

methicillin and all “As MRSA strains that originated in the community enter health care settings, the epidemiologic and molecular features of MRSA are evolving, and the microbiologic characteristics of isolates from patients with community-associated MRSA (CA-MRSA) and healthcare-associated MRSA (HA-MRSA) infections are no longer as distinct as they were initially,” she said. Initially, many MRSA experts suspected that community cases of MRSA were the result of exposure to MRSA in a health care setting. CA-MRSA is epidemiologically defined as MRSA with onset in the community in a patient that lacks established MRSA risk factors, such as recent hospitalization or surgery, long-term care, dialysis, indwelling catheters and history of previous MRSA infection. Gorwitz described the microbiology of MRSA isolates seen in the community, explained the prevalence of S. aureus infections and suggested various methods to control MRSA transmission in the community. Spectrum of S. aureus “The clinical spectrum of S. aureus in the community includes asymptomatic colonization, skin infections and, less commonly, severe and invasive infection,” Gorwitz said. A nationally representative survey, conducted by the CDC, evaluated the prevalence of nasal colonization with S. aureus in the United States in 2001 and 2002 and found that, overall, the prevalence of S. aureus nasal colonization was 32.4%. In contrast, the prevalence of MRSA nasal colonization was 0.8% and was associated with age older than 60 years and female sex. A follow-up study is being conducted to determine whether the prevalence of nasal colonization with MRSA has increased. Community strains may also be more likely to cause disease, but less likely to cause colonization, according to Gorwitz. Regardless of the available data, she stressed that several important questions about MRSA colonization remain. For one, is MRSA colonization increasing in the community? According to Gorwitz, some studies suggest it is. Data by Creech et al, published in Pediatric Infectious Diseases Journal, showed that among pediatric patients attending health maintenance visits, MRSA colonization jumped from 0.8% in 2001 to 9.2% in 2004. Another unanswered question with limited data is the association between MRSA colonization and risk for infection compared with methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA). A study by Ellis et al, published in Clinical Infectious Diseases, indicated that risk of S. aureus skin infection was 38% among soldiers with MRSA colonization compared with 3% in MSSA colonized soldiers.

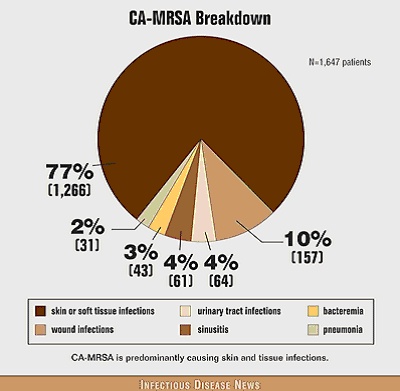

The CDC’s Active Bacterial Core Surveillance (ABCs) program is a population-based surveillance component of the Emerging Infections Program Network that is designed to study the incidence and epidemiological features of bacterial infections and track drug resistance in the nation. Participating sites identify culture-confirmed cases of MRSA infection in their area and classify them as CA-MRSA or HA-MRSA. The first phase of the study was conducted in 2001 and 2002 in areas of Maryland, Georgia and Minnesota and phase 2 began in 2004 and expanded to areas of nine states: California, Colorado, Connecticut, Georgia, Maryland, Minnesota, New York, Oregon and Tennessee. ABCs total study population consists of 16.2 million people. The first phase study results, published by Scott Fridkin and colleagues in The New England Journal of Medicine, showed that CA-MRSA infections presented most commonly as skin and soft tissue infections. Of 1,647 patients with CA-MRSA, 77% had skin or soft-tissue infections, 10% had wound infections, 4% had urinary tract infections, 4% had sinusitis, 3% had bacteremia and 2% had pneumonia. The CDC recently collaborated with a group called EMERGEncy ID Net, a network of 11 academic emergency medicine departments, on a study to evaluate the epidemiology of skin infections among adults presenting to emergency departments. Data by Moran et al, presented at the May 2005 Society for Academic Emergency Medicine meeting, showed that MRSA was isolated from 59% of skin infections from which cultures could be obtained. This prevalence ranged from as low as 15% in New York to as high as 74% in Kansas City. The researchers also determined that MRSA was the most commonly identified organism in purulent skin infections in all but one of the participating sites. Among MRSA isolates, 98% carried genes for the Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL) toxin and 97% were USA300. MSSA was isolated from 17% of skin infections; 42% of susceptible strain isolates were PVL-positive and 31% were USA300, according to Gorwitz. “Severe and invasive manifestations are less common than skin infections, but do occur, and include presentations such as necrotizing pneumonia and empyema, sepsis syndrome, disseminated infection with septic emboli, musculoskeletal infections (such as pyomyositis and osteomyelitis), necrotizing fasciitis, purpura fulminans and toxic shocklike syndrome,” she said. ABCs data showed that the incidence of invasive MRSA infections jumped from 19 to 33 per 100,000 in Atlanta and from 40 to 115 per 100,000 in Baltimore over the three-year period between 2001 and 2004. The proportion of those invasive MRSA infections due to CA-MRSA also increased from 13% to 17% in Atlanta and from 7% to 24% in Baltimore. “Incidence of invasive MRSA infections and invasive community-associated MRSA infections may be increasing,” she suggested. In the 2003-2004 influenza season, the CDC solicited reports of S. aureus community-acquired pneumonia following influenza-like illness, according to Gorwitz. Seventeen cases were reported, 15 of which were MRSA. Of the 10 MRSA isolates available for research, eight were USA300-0114. The patients’ ages ranged between 8 months and 62 years (mean 21 years), 71% (12) had no underlying illness and 71% (12) had laboratory-confirmed influenza. Of the total patient population, 94% (16) were hospitalized, 81% (13) were admitted to the ICU, eight were intubated and five patients died. MRSA management CA-MRSA outbreaks are often first detected as clusters of abscesses that are often confused with spider bites. Factors that facilitate CA-MRSA transmission include the five C’s, according to Gorwitz: crowded living conditions, frequent skin-to-skin contact, compromised skin surface, contaminated surfaces and shared items and barriers to maintaining cleanliness. The last “non-C” item associated with transmission is antimicrobial use. CA-MRSA outbreaks have been described among sports participants, inmates, military trainees, children in day care centers, Native Americans, Alaska Natives and Pacific Islanders, men who have sex with men and, more recently, hurricane evacuees in shelters, tattoo recipients, and individuals living in a rural population with a high prevalence of crystal methamphetamine use, according to Gorwitz. The CDC held a MRSA experts’ meeting to establish reasonable strategies for control and clinical management of MRSA in the community. A document describing strategies based on the input from MRSA experts and a thorough review of available data has recently been posted to the CDC Web site. The group determined that although it has not necessarily been the standard of practice, it is important for clinicians to culture skin infections. This can be beneficial for monitoring patient management and establishing the local prevalence of antimicrobial resistance in specific geographical locations, according to Gorwitz. However, Gorwitz said that molecular typing or toxin typing should not be used to guide management due to the lack of data. In terms of treatment, incision and drainage should be routine for purulent skin lesions, and empiric antimicrobial therapy may be needed in some cases. It is also important to use local data to base treatment because the susceptibility of S. aureus to methicillin and other agents may vary geographically, according to Gorwitz. More data from controlled clinical trials are needed to identify optimal treatment strategies. “A variety of alternative agents have been proposed; all have advantages and disadvantages, but the key point is that more data are needed to identify optimal treatment,” she said. Participants in the CDC experts’ meeting also discussed the role of regimens to eliminate S. aureus colonization in the control of MRSA in the community. Efficacy data are not available and the emergence of resistance to agents used for decolonization is a concern. “However, taking into account that efficacy data are lacking, meeting participants felt that it may be reasonable to administer decolonization regimens, after optimizing basic control strategies, in patients with recurrent infections and in situations where there is ongoing transmission in a closely associated cohort, such as a household.” However, appropriate regimens, including agents and schedules, have not yet been established for decolonization in community settings. Patient education is a critical component for MRSA management and prevention. Physicians should educate their patients on what they can do to prevent spreading the infection to others. “Educating people to maintain hygiene and maintain a clean environment is important. We need to utilize the variety of educational resources available,” she said. Equally important is maintenance of adequate follow-up, the group suggested. Researchers suggested a few public health interventions, such as enhancing MRSA surveillance, targeting empiric therapy to the pattern of outbreak strains, educating physicians and patients about wound care and wound containment, promoting enhanced personal hygiene, limiting sharing of personal items and, in some situations, excluding patients from certain activities. “Various studies are under way and more are needed to determine the best methods for control and prevention of MRSA in the community. However, strategies focusing on increased awareness, early detection and appropriate management, enhanced hygiene and maintenance of a clean environment appear to have been successful at limiting transmission,” she concluded. The CDC’s strategy for MRSA control is available on the CDC Web site. For more information:

|