|

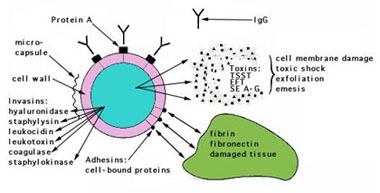

S. aureus expresses many potential virulence factors: (1) surface proteins that promote colonization of host tissues; (2) invasins that promote bacterial spread in tissues (leukocidin, kinases, hyaluronidase); (3) surface factors that inhibit phagocytic engulfment (capsule, Protein A); (4) biochemical properties that enhance their survival in phagocytes (carotenoids,catalase production); (5) immunological disguises (Protein A, coagulase, clotting factor); and (6) membrane-damaging toxins that lyse eukaryotic cell membranes (hemolysins, leukotoxin, leukocidin; (7) exotoxins that damage host tissues or otherwise provoke symptoms of disease (SEA-G, TSST, ET (8) inherent and acquired resistance to antimicrobial agents.

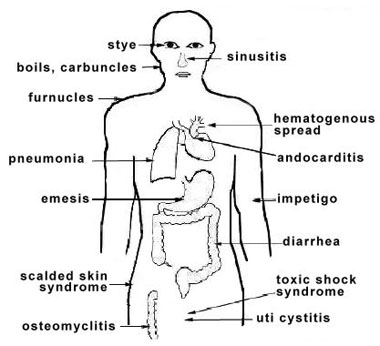

FIGURE 2. Virulence determinants of Staphylococcus aureus For the majority of diseases caused by S. aureus, pathogenesis is multifactorial, so it is difficult to determine precisely the role of any given factor. However, there are correlations between strains isolated from particular diseases and expression of particular virulence determinants, which suggests their role in a particular diseases. The application of molecular biology has led to advances in unraveling the pathogenesis of staphylococcal diseases. Genes encoding potential virulence factors have been cloned and sequenced, and many protein toxins have been purified. With some staphylococcal toxins, symptoms of a human disease can be reproduced in animals with the purified protein toxins, lending an understanding of their mechanism of action. Human staphylococcal infections are frequent, but usually remain localized at the portal of entry by the normal host defenses. The portal may be a hair follicle, but usually it is a break in the skin which may be a minute needle-stick or a surgical wound. Foreign bodies, including sutures, are readily colonized by staphylococci, which may makes infections difficult to control. Another portal of entry is the respiratory tract. Staphylococcal pneumonia is a frequent complication of influenza. The localized host response to staphylococcal infection is inflammation, characterized by an elevated temperature at the site, swelling, the accumulation of pus, and necrosis of tissue. Around the inflamed area, a fibrin clot may form, walling off the bacteria and leukocytes as a characteristic pus-filled boil or abscess. More serious infections of the skin may occur, such as furuncles or impetigo. Localized infection of the bone is called osteomyelitis. Serious consequences of staphylococcal infections occur when the bacteria invade the blood stream. A resulting septicemia may be rapidly fatal; a bacteremia may result in seeding other internal abscesses, other skin lesions, or infections in the lung, kidney, heart, skeletal muscle or meninges.

FIGURE 3. Sites of infection and diseases caused by Staphylococcus aureus Adherence to Host Cell

Proteins Evidence that staphylococcal

matrix-binding proteins are virulence factors has come from studying

defective mutants in adherence assays. Mutants defective in binding to

fibronectin and to fibrinogen have reduced virulence in a rat model

for endocarditis, and mutants lacking the collagen-binding protein

have reduced virulence in a mouse model for septic arthritis,

suggesting that bacterial colonization is ineffective. Furthermore,

the isolated ligand-binding domain of the fibrinogen, fibronectin and

collagen receptors strongly blocks attachment of bacterial cells to

the corresponding host proteins. |